Cost of Life

Cost of Life is a top down hack and slash game meant to satirize the predatory practices of the American health insurance industry.

The game was made by a team of four students for an Alternative Game Development class. It was completed over the course of three months.

My role on the team was as Vision Holder and Lead Designer. I also did a good bit of the art, which was a fun new experience for me. We made the game in GameMaker studio. It was a great lesson in developing a game where fun wasn’t the main goal.

The Idea

It was a cloudy and grey spring afternoon. I was walking my dogs with my wife when I stepped and missed the sidewalk. I fell hard onto the poop bags I was holding. They of course popped, covering my side with dog feces. Worse than this, my ankle twisted badly and I had to hobble the rest of the way home.

It was the worst sprain I had ever had, so I went to urgent care to make sure I didn’t have a hairline fracture. They did an X-Ray, and all was well. Until, the bill came. It was around $800. Which, as a broke college student, was nothing to shake a stick at.

As an international student, I had to have the health insurance provided by the school. It cost about $1000 a semester, and was the worst insurance of all time. They covered nothing. That nothing included this X-Ray.

I vented out my frustration by designing Cost of Life. Take that insurance companies.

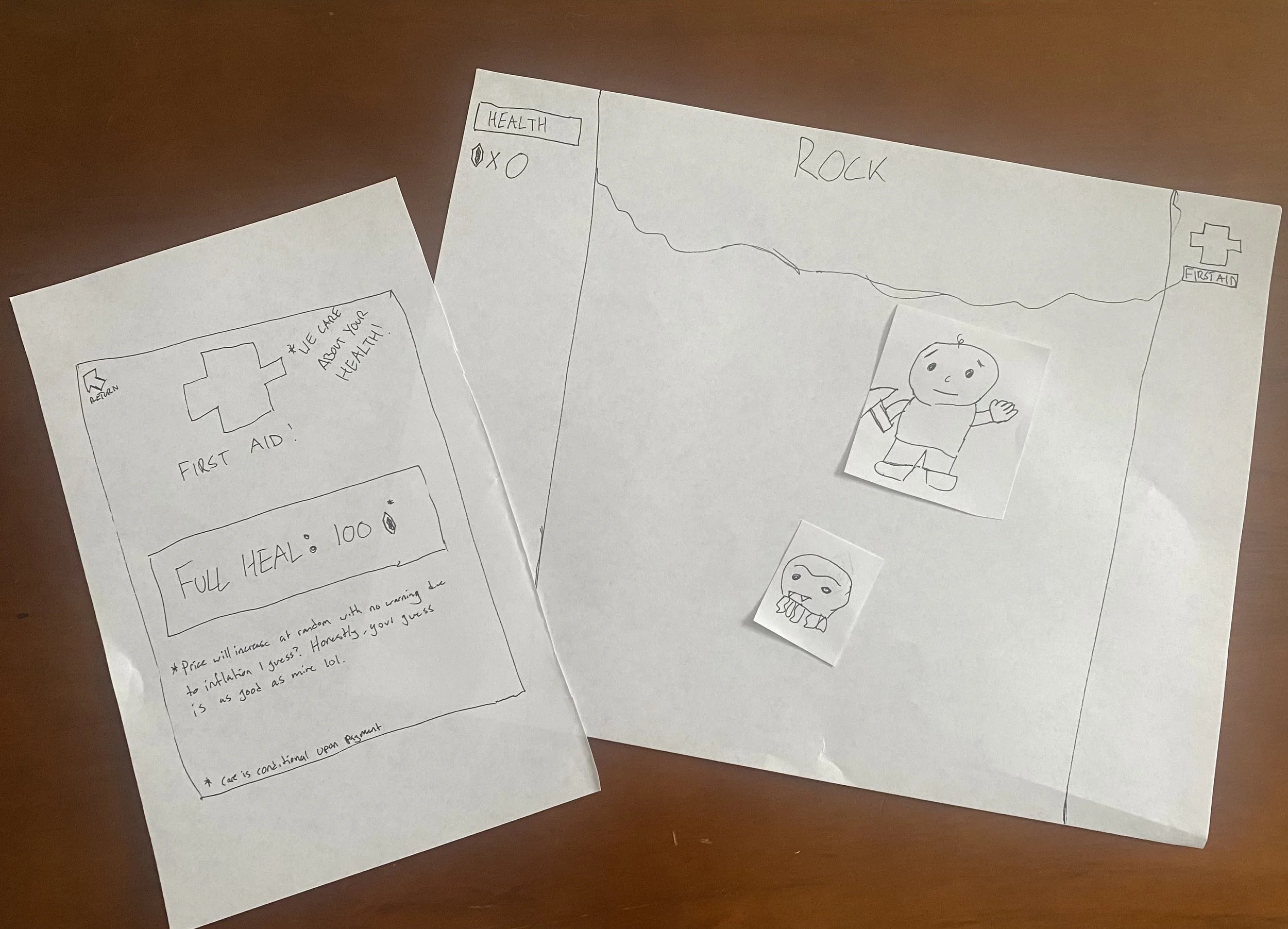

The original idea, as demonstrated in this incredible paper prototype, was to have the players chip away at a single giant rock as monsters attacked them from the opposite end. They would collect gems, and have to spend those gems to heal themselves. The price of healthcare would originally fluctuate at random to illustrate hidden costs and ever changing rates.

The gameplay and systems were meant to literally symbolize how health insurance often feels like beating your head against a rock. You pay insurance premiums, then have to pay on top of those premiums to receive actual healthcare. You then have to work endless hours to afford the healthcare you received. It’s a vicious and unfair cycle.

The game was never meant to be fun, but to feel like a slog.

Changes Made

Our team prototyped the idea in engine and took it to play tests. The immediate feedback was that the symbolism wasn't entirely apparent. I decided that instead of relying on contextual understanding of the frustrations inherent in medical insurance, we would need to tell more of a story.

I figured the best way to do so would be to tell a simple story about someone taking on an extra job to pay off the medical debt their father garnered in a work accident.

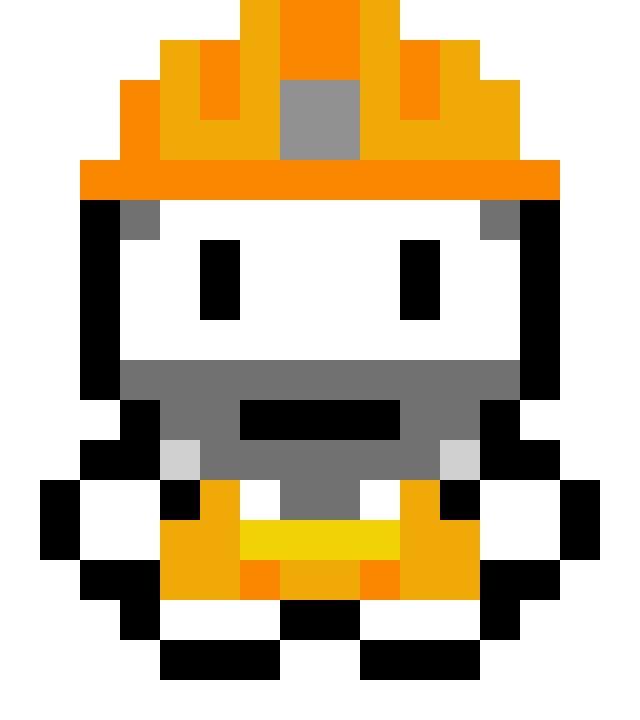

I also wanted to ensure that the games messaging wasn’t accidentally blaming doctors for the way they charge patients. Doctors are not the problem, insurance companies are. This led me to create the character of Bill Collector the bill collector.

The other big thing we changed was the games progression, or its lack thereof. Instead of slamming the player into the same rock over and over, I thought it might be more meaningful to introduce a “goal” for the player to reach. In the opening narrative, I established that “500 Gems” was the amount the player needed to reach to pay of their father’s debt. This provided the player something tangible to shoot for.

Of course, it was impossible to acquire this many gems. Playing the game naturally depleted the players health, so they would have to heal, which meant they would lose their gems. You can never escape insurance.

We also added three levels full of rocks and monsters for the player to clear. We did this to add a faux sense of progress. If the player clears the third and most difficult level, the screen shakes, and the player is crushed by a rock. Another workplace accident. Another medical bill. Rats.

Bill, seen here with his giant sack of gems, is a giant sack of gems himself. When the player healed in the game, they would be greeted by a doctor, who would heal them for 5 gems. A few moments later, the gameplay would be interrupted by the arrival of Bill, who would let players know they had an overdue balance from their healthcare visit. Bill would then take the rest of the gems players had earned, putting them back at square one. He’s a real smug piece of work that Bill.

The original cycles of injury, healthcare, and bills, now felt a little more purposeful. In play tests I watched players frustratingly realize they had lost all their progress due to Bill. Sometimes it would even cause them to stop playing. This meant our games messaging was working.

Lessons Learned

After all was said and done, I was pretty satisfied with the game we made. I honestly think the biggest issue we had was adding too many elements to the game just for the sake of fun. As we added levels, we naturally wanted to add more complex enemies. I tried to reign most of it in, but I think these extra features ended up detracting from the overall messaging.

Trying to design and build something that actively goes against fun often felt unnatural. It was a great lesson in restraint, and designing with a distinct purpose. I constantly had to ask myself if the design choices we were making were serving our overall purpose.

This game also allowed me to grow in game design areas I was less familiar with. I became pretty adept at coding, and quick art. I learned to dip into the engine a little heavier and solve some of my own problems without relying on the help of an engineer.

Thanks Cost of Life, and thanks GameMaker.